From Unilever’s thinking on areas from M&A to innovation, we present the five things you need to know from the FMCG giant’s investor event.

Unilever’s leadership team, headed by CEO Alan Jope, convened at the FMCG giant’s North American offices last week for the Knorr and Magnum owner’s investor conference.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The annual event was the first led by Jope, the Unilever veteran who took the helm at the business at the start of this year.

In his first ten months in the hot seat, Jope has followed the thrust of the strategy drawn up by his Dutch predecessor Paul Polman, with the Scotsman on Thursday (14 November) talking up Unilever’s “vision” to be “the leader in sustainable business globally”.

Addressing analysts in New Jersey, Jope said: “We aim to demonstrate once and for all that our purpose-led future-fit model drives superior outcomes, superior business performance.”

Nevertheless, there has been (and will be) change at Unilever and this (and much more) was discussed at the event last week.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataPurpose “at the heart” of Unilever’s strategy

At last year’s investor summit, held in Mumbai just days after Jope was announced as Unilever’s soon-to-be CEO, he highlighted how, under his watch, the company would “remain a purpose-led company”.

‘Purpose’ has become the industry buzzword when describing a company’s overall mission, with many an executive often tying the term to a business’ sustainability agenda.

There is, though, no mistaking Unilever’s – and Jope’s – belief that doing business sustainably is also good business.

He told analysts on Thursday: “Since April – and this is a bit you’ve not been exposed to yet – our sustainability strategy and our business strategy no longer sit separately but they’re now one integrated business and sustainability strategy.”

The investment community once had a very sceptical view of sustainability but more investors are becoming more engaged, not least because of the associations between sustainability issues and business risk.

That said, while more investors are more persuaded by, for example, the negative impacts the climate crisis could have on business, some believe the likes of Unilever and Danone may be placing too much emphasis on sustainability issues.

“Jope is more enthusiastic talking about sustainability, digital and the talent agenda than the nuts and bolts of growth drivers, cost savings and portfolio choices. He is convinced that consumers are preferring purpose-driven brands, that markets are fragmenting and that the age of network TV-led mass marketing is over. We don’t entirely agree,” Jefferies analyst Martin Deboo wrote in a note to clients after attending the Unilever investor event.

Dissatisfaction with sales growth

Unilever sees ‘purpose’, Jope underlined, “as a source of competitive advantage” – and, as such, central to the company’s strategy to grow its sales.

And there’s no question Unilever’s recent top-line growth has been a hot topic among investors and equity analysts covering the business.

Unilever targets annual sales growth, on an organic basis, of 3-5%. In 2018, sales by that metric grew 3.2%.

During his months in charge, Jope said he had met “over 100 investors in Unilever many multiple times” and had sought to underline how “growth is our priority”.

Surveying Unilever’s results against a series of financial targets the company set out in 2017 – including on organic sales – Jope said the company’s performance could be described as “greens across the board with one exception, which is top-line growth, which is an amber and it’s not where we want it to be”.

He added: “I’m not happy about where we are right now. It is not my goal to remain in the bottom half of our multi-year [sales target] range. But I am clear on some of the things that we need to do.”

The Unilever chief told analysts the company would look to accelerate its growth by, for example, moving its portfolio into “higher-growth segments”, as well as “leveraging our growth geographies more fully” and “winning in high-growth channels”, efforts Jope added would be “all underpinned by putting purpose at the centre of what we do.”

Unilever still faced questions about its sales strategy, with JPMorgan analyst Celine Pannuti asking how long it would be before the company would see the fruits of its initiatives – and whether it would take asset disposals to “really kick-start the growth momentum”.

Jope replied: “We profoundly believe that there’s trapped growth in the business we have today. And we have a very good sense of why we’re operating in that 3-4% range and not higher.”

A shift on innovation

One of the planks of Unilever’s strategy to grow sales is innovation, both on incumbent brands and in developing new brands.

And it was on innovation that Jope made some of his most eye-catching comments and provided some clear indications of how Unilever will change its ways of working under his stewardship.

Jope’s comments on innovation also spoke to that age-old challenge FMCG multinationals face – is innovation best done locally or centrally.

Three years ago, at Unilever’s 2016 investor summit, the company, describing its then new Connected 4 Growth strategy, looked to be putting just as much importance on trying to be as “local” as possible as it was being global and trying to benefit from scale.

At the time, Polman argued Unilever had become “a little bit too centralised and, in some cases, far too removed from the consumers we wanted to serve”. He added: “When you see who is growing, it is local competitors. They are closer to consumers in these markets.”

In New Jersey last week, Jope suggested a change in emphasis. “Unilever’s default model is a decentralised model. If you took controls off of Unilever, everything would default to the country axis. We’re very proud of our long local histories in markets. I think during C4G we allowed the pendulum on innovation to swing too far to local and we generated lots and lots and lots of well-intentioned but necessarily small local projects,” he asserted.

“We are getting much more top-down on identifying the global-priority, big-hit innovation. We’ve not actually done that historically. We’ve allowed their innovation programme to be a little bit too much bottom-up, and we’re going to shift to a much more top-down.”

A live example of this change in approach is the launch last week across more than 20 countries of the plant-based Rebel Whopper burger by Unilever and its The Vegetarian Butcher unit through Burger King outlets.

How Unilever is thinking about M&A

Unilever’s M&A strategy has, for many years, been the subject of debate in the investment community, with Polman regularly, for example, fielding questions about whether the consumer-goods group would consider quitting the food industry.

Some would still favour such a move. In a note issued to clients before the Unilever investor event, Jefferies’ Deboo described how the company’s disposals of food assets in recent years had been “a long goodbye [that] leaves Unilever stuck in low-growth, centre-store categories”, adding the bank “still dreams about an ultimate combo with Colgate”.

However, Deboo suggested how Unilever’s options for its combined food and refreshments division may be limited. “Exiting tea in developed markets or mayo/dressings would be only modestly dilutive and would get Unilever out of tricky categories, without much prejudice to punching power in emerging markets,” he wrote.

“A full or semi-exit from food and refreshments would be heavily dilutive and would only make sense, in our view, as an enabler of step-change expansion into home and personal care, where we continue to fantasise around an ultimate Unilever/Colgate combo. But with Kraft [Heinz] holed below the waterline, who now is the natural consolidator of developed-markets foods assets?”

In New Jersey, Unilever’s management was pushed on the perennial question of food and non-food continuing to be bedfellows. Jope said Unilever’s “operational backbone” benefited from having both businesses remain in the same company. “We see continuing efficiencies and value in running the businesses together.”

That’s not to say Jope did not comment on Unilever’s M&A strategy. He was pretty explicit about the group’s plans to ease off on the number of acquisitions it will make and look more closely at making disposals.

“We are still open to M&A large and small, we’ll continue to set demanding criteria, run a rigorous process, be highly disciplined in valuations – but you may well notice a slowdown in the number of acquisitions going forward. At this time of particularly high valuations, we’re going to focus on the 34 acquisitions that we’ve already completed in the last five years and how we can realise full value from those,” he said.

“That’s one side of the ledger but portfolio shift is also about disposals. Perhaps we’ve not been as active in this space as we have in the past. We do want to be more strategic here. We know that we have structurally lower-growth segments in the business and we’re in the process of carrying out uncompromising evaluation with an open mind. There are no sacred cows.”

However, Jope added: “Please don’t prove us for specifics in the next two days. We won’t be giving any more detail until we’ve completed our disciplined work looking at what brands or businesses might fall into that category.”

That hasn’t stopped analysts speculating, with lower-growth food assets put forward as parts of the Unilever portfolio that could, one day, be sold.

“Unilever made it clear that the focus in fiscal year 2020 is more on potential divestments than investments,” MainFirst analyst Alain Oberhuber wrote after attending the investor event. “The categories which are not performing currently are the North American dressings business, the US ice cream business and the black tea business. The jury is out whether these brands can be fixed. If they cannot be fixed and the category is not interesting, they will be divested.”

It is important to note that Unilever made no on-the-record comments during the conference about the potential fate of any parts of its portfolio, let alone food.

Jope did, however, again put forward Unilever’s desire for each of its brands to have “purpose” and – again – suggested the company would offload those that did not, although it is clear he is giving all parts of the portfolio team a chance to find their cause.

“What I will say does not work is forcing the pace. If we set a deadline that says by March, we want all brands to be very clear on the purpose that they’re going to stand for, what we would end up with in February and March is a series of trivial or fake associations between a brand and something that matters in society. We’re going to give our brands quite a bit more time to see if they can find something important to campaign on and stand for.

“I really think there’s not a category where we would say that category is incapable of being a carrier for purpose. But, as we do our review of whether there are businesses in the portfolio where they might be better owned by someone else, and the primary lens will be long-term growth momentum, but a secondary lens will be ‘are we making progress on making this a more purposeful business?'”

Where Unilever believes it can grow in food

On food, there is no question Unilever is battling some low-growth areas and has, in recent quarters, faced specific challenges in categories like dressings in the US.

However, the Hellmann’s mayo maker has continued to invest in food, adding businesses through bolt-on M&A, such as The Vegetarian Butcher in the Netherlands, Good People in Romania and Olly Nutrition in the US.

Hanneke Faber was appointed the head of Unilever’s combined food and refreshments arm in May, a year after joining from retailer Ahold Delhaize to lead the group’s European operations.

Speaking in New Jersey, she sought to underline the fact less than half the division’s sales are in emerging markets is an “opportunity” and made the link between some of the trends shaping food consumption worldwide – concern over health and over the environment – and Unilever’s ‘purpose’ agenda. “I think this is the most exciting business to work in where we can really do well by doing good,” she said.

In an echo of Unilever’s comments at its 2018 investor day, Faber also talked up the opportunities she sees for Unilever Food Solutions, the unit selling to the foodservice channel.

Surveying Unilever’s overall food and refreshments arm, Faber said: “We have four clear growth choices: accelerate the out-of-home channel growth; a shift in our portfolio; ‘every brand a movement’, which is what we call purpose; and winning innovation.

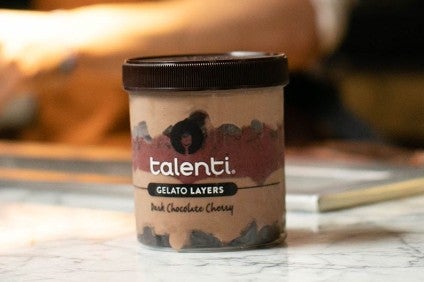

“We are playing in a number of categories that are actually very healthy. We need to get more out of those. Impulse and premium ice cream, scratch cooking – the bouillons, seasonings, herbs and spices – herbal and green tea 6%. Snacking, a huge category. We’re actually quite small, but we have some interesting efforts. Then growth spaces. Vegan and vegetarian, plant-based to meat replacement – a big big space and personalised wellness, also growing fast although yet quite small.”

It is clear Unilever has pinpointed parts of the food industry where it thinks it can win. It would not be a surprise, however, if some parts of Unilever’s food portfolio are areas where the group’s new emphasis on disposals plays out.