To be frank, given the opposition, it didn’t come as a huge surprise when The European Commission announced yesterday (2 October) it was delaying the introduction of EUDR, its new rules to tackle deforestation.

EUDR, or EU Deforestation Regulation, was announced in late 2021 and drawn up to help cut greenhouse gas emissions and limit biodiversity loss.

Under the regulations, companies selling cocoa, coffee, palm oil and other products in the EU would need to prove their supply chains do not contribute to the destruction of forests.

Lauded by campaigners, EUDR, which was due to come into force before the end of this year, was criticised by some in origin countries and, while in the main publicly welcomed by industry, Brussels faced pressure from big business and politicians (including in Washington) on the timetable.

Last week, European farming body Copa-Cogeca and meat-industry organisation the European Livestock and Meat Trading Union (UECBV) co-signed a letter sent by sector bodies across a range of industries, including media, packaging and timber, arguing the implementation of EUDR, before the end of the year is “simply unfeasible”.

In a statement yesterday, The European Commission said it is now proposing giving companies an extra 12 months of “phasing-in time”. If the European Parliament and European Council back its revised plan, EUDR would kick in on 30 December 2025 for large companies and 30 June 2026 for smaller businesses.

"Given the EUDR's novel character, the swift calendar, and the variety of international stakeholders involved, the Commission considers that a 12-month additional time to phase in the system is a balanced solution to support operators around the world in securing a smooth implementation from the start," the European Commission said.

Copa-Cogeca, UECBV and its co-signatories issued their own swift response, in which they said “welcomed” the postponement, adding: “While we fully support the regulation’s objective to combat global deforestation, it is crucial to ensure that it is implemented under the right conditions to be effective and feasible.”

Brussels’ decision attracted fierce criticism in campaign circles, with some NGOs not just angry with the delay but fearing the postponement may provide an opportunity for certain stakeholders to weaken the planned rules.

Glenn Hurowitz, the founder and CEO of US-based advocacy group Mighty Earth, says EUDR is "perhaps the most important international forest policy of the last decade".

He pins the delay on lobbying by a handful of major corporations. "Everyone from smallholder farmers to the bulk of responsible companies were ready for EUDR compliance," Hurowitz says. "A few giant animal feed and Canadian forest companies moaned that even while rubber, palm oil, and cocoa farmers making as little as a few hundred dollars a year could comply, they couldn't figure it out – but that was just normal lobbyist moaning that shouldn't have gotten the traction it did."

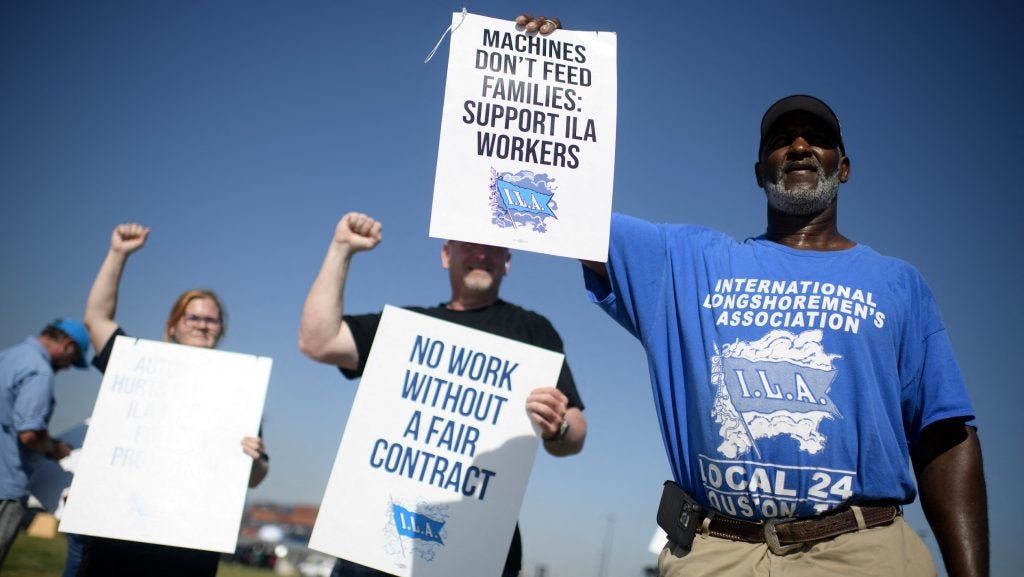

He added: "But at a deeper level, this setback is a product of much of the funding for the environmental community going towards technical compliance issues – while agribusiness was putting angry farmers in the streets. There's been great work by Fern NGO and many civil society allies in Europe and around the world, but it needs to happen at scale commensurate with the challenge and opportunity, and especially focused on EU member state governments.

"We need to scale up high-level lobbying, grassroots advocacy, and communications. The good news is that I think this really is a delay rather than an underhanded cancellation. So there's a chance to do that quickly. That doesn't mean there aren't threats. The EU could in its postponement also weaken the regulation further."

So far, there has been no explicit call by any company nor member organisation for a dilution of EUDR. The PR blowback would be fierce.

But. in the statement signed by Copa-Cogeca and UECBV, the associations, which also included the European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation, said: "The focus must now shift to addressing the practical challenges associated with the EUDR’s implementation to prevent uncertainties and avoid supply chain disruptions."

A fortnight ago, the European Cocoa Association (ECA), a trade body that represents cocoa buyers, sellers and traders in the EU including Barry Callebaut, Cemoi and Natra, called for a six-month delay to the implementation of EUDR.

Matthijs de Meer, the ECA's senior manager for EU Affairs and sustainability, said the association had wanted "a formal delay, not for a re-opening of the substance of the regulation".

"We called for this delay as we saw that key documents and tools were not ready or sufficiently developed," de Meer told Just Food. "We have supported the EUDR and will continue to work towards compliance."

Interestingly, one of the ECA's members, Barry Callebaut, the world's largest B2B chocolate producer, issued its own statement, telling Just Food it "regrets" the European Commission's proposal.

"In our view, EUDR requires a lot of effort and resources for compliance from all stakeholders along the supply chain, however these efforts are important to drive the sustainable transformation in the cocoa supply chain," the Switzerland-based group said. "The legal pathway to formally postpone the application date for EUDR bears a risk of changes to the substance of the regulation, which can have consequences on the operational implementation of EUDR."