The US Food and Drug Administration's rules on food inspection and product recalls must be updated to avoid a repeat of the 2022 infant formula crisis, a new report has said.

Released today by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG), the assessment concluded the FDA had policies that were "inadequate to identify risks to the infant formula supply chain".

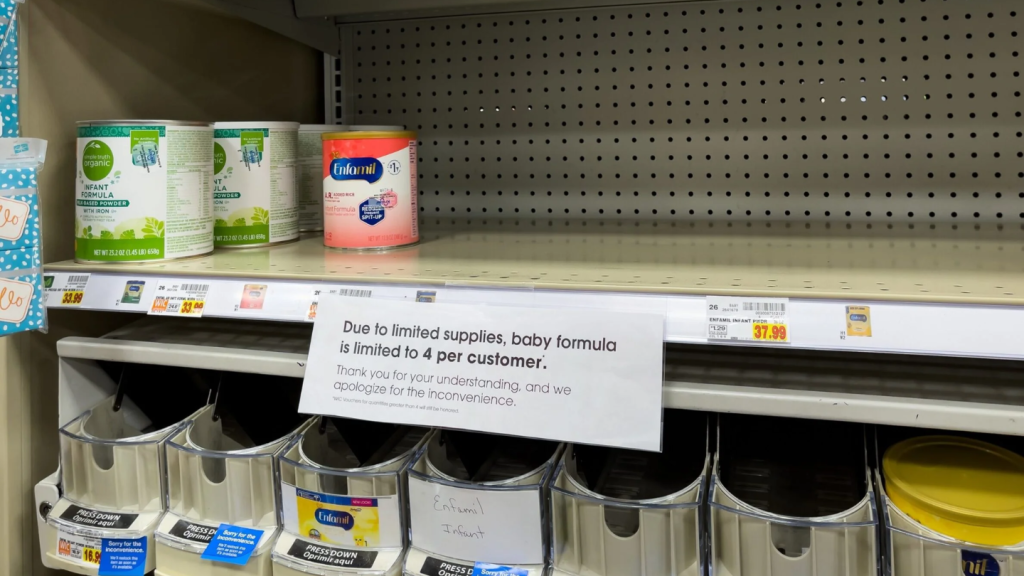

In February 2022, consumers across the US experienced major shortages of infant formula when the country's largest baby food producer, Abbott Laboratories, shut down its plant in Sturgis, Michigan, following worries over salmonella and cronobacter bacteria contamination.

The report notes that a whistleblower complaint from Abbott was sent to the FDA in October 2021. However, FDA officials and senior management said they did not receive the complaint until February 2022.

The complaint was sent electronically to the FDA but "not escalated to senior leadership due to a lack of complaint escalation policies and procedures".

According to the OIG, the FDA's policies brought about "delays in its response to the February and October 2021 whistleblower complaints", and "investigators not receiving information from a relevant consumer complaint while they were conducting an inspection".

It also meant inspectors did not know "how and when to initiate the 2022 for-cause inspection during the public health emergency".

The watchdog added: "If FDA had adequate policies and procedures, it could have identified underlying problems at the Abbott facility and required Abbott to correct them.

While the OIG acknowledges the food safety authority "took some action during the facility inspections and conducted follow-up inspections in accordance with federal regulations and internal policies and procedures", it stressed that its own inspection shows "more could have been done" in the days preceding Abbott's food contamination scare.

OIG issues recommendations for FDA

Following its audit, the OIG set out nine recommendations for the FDA to improve its recall and inspections processes.

These include "cross-training staff on whistleblower policies and procedures" and deploying new policies that involve regular reporting of status of whistleblower complaints to management.

The OIG has called for new policies that could be used in future crises to help the FDA "identify how and when it is necessary to conduct mission-critical inspections and ensure that mission-critical inspections are conducted in a timely manner".

It also recommended the federal agency "continue to seek legislative authority to require infant formula manufacturers to notify and provide the bacterial isolate to FDA every time a product sample is found to be positive for cronobacter or salmonella", regardless of whether the products had left the factory.

The FDA has scheduled a complete restructure of its food division, starting from 1 October. The modernisation will see the body take on a "unified Human Foods Program (HFP), headed up by Deputy Commissioner James Jones, who will look to consolidate several FDA food centres and offices under one unit.

Speaking to Just Food last week on the proposed changes, Frank Yiannas, former deputy commissioner for food policy & response at the FDA said the changes marked a vast improvement, especially when it came to the organisation's food budget.

“Under the new structure, the deputy commissioner now owns the entire foods programme budget," he said.

"This is something new that none of the past deputy commissioners… ever had. Oversight of the entire foods program budget is also a great thing to ensure alignment on how resources are used.”

Despite the changes, Yiannas added there were “objective metrics" the FDA should focus on to "help us determine if the reorganisation is delivering on promised improvements”.

Some of those metrics included boosting the FDA's number of inspections, shortening the time it takes for the body to approve new food products and writing new standards of identity.