Cocoa prices have reached record highs as a drop in the global supply leaves chocolatiers scrambling to secure the essential raw ingredient.

GlobalData, Just Food's parent, predicts a fall in supplies of around 8% in the 2023-2024 season compared to the previous 12 months, with the losses primarily attributable to problems plaguing the two biggest suppliers – Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana.

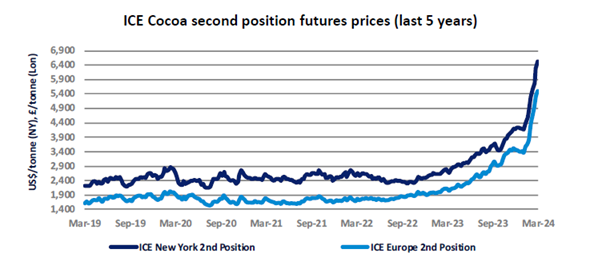

The limited availability has translated into an uncertain market with rapidly increasing prices. “Over the last twelve months to the third week of March, cocoa bean prices have increased by 166% and 189%, respectively, in the New York and London cocoa bean futures markets," GlobalData agribusiness analyst Gerard Stapleton says. "Over the last eighteen months (since October 2022) the respective price increases were 221% and 223%. Before then, prices had remained relatively flat over the preceding three-and-a-half years.”

Falling cocoa supplies mean rising prices

Speaking to Just Food, a Lindt & Sprüngli spokesperson acknowledges the difficulties the company is experiencing in buying cocoa. “Cocoa beans, sugar, and milk are among our most important raw materials. These raw material prices are always subject to fluctuations and rising costs are a challenge. This applies in particular to our most important raw material, cocoa, the price of which almost doubled over the course of the last year, reaching a new all-time high on the London commodity futures exchange.”

In 2023, Lindt recorded sales of Sfr5.20bn ($5.87bn), up 10.3% year-on-year, while net income was up 17.9% at Sfr671.4m.

But the Switzerland-based company admitted saw most of its growth come from price increases. It put prices up by 10.1% in 2023.

Globally, the predicted net output for the 2023-2024 season is 4.5 million tonnes, a reduction of around 340,000 tonnes compared to last year. Stapleton calls it “a significant shortfall”, noting that “there is going to be some impact on demand.” He expects this to be a reduction of around 4%, as shoppers are deterred by higher price points.

Edward Bergen, consumer analyst at consultants FutureBridge, says even though shoppers will experience the impact of cocoa prices, the full force of the problem will not be immediately obvious on supermarket shelves.

“It has been passed on to the consumer but it looks like the industry is protecting the consumer a little bit. The average increase is roughly in line with general inflation numbers for the food industry – around 20%.”

Why is cocoa production lower?

Around 40% of cocoa beans globally come from Cote d’Ivoire, while 15% come from Ghana. Supplies are expected to drop by 18% and 19%, respectively, leaving a significant drawdown, despite production growth from other suppliers.

Considering the reasons behind the decline, Sukanya Nag, food technologist and innovation and strategy consultant at FutureBridge, tells Just Food: “There are multiple factors at play in the cocoa industry, starting with poor weather conditions: El Niño is currently going on as well as drought conditions, and the effects of the Harmattan winds have worsened due to El Niño, with drier air and dry conditions.

“Then there are crop diseases that were seen across 2023. Entire crop yields got affected by them and there was a projected decline of almost 10%.”

Nag is referring to two diseases that have wreaked havoc on cacao trees: black pod disease and cacao swollen chute virus. They had been present in Ghana in recent years and have now spread to Cote d’Ivoire.

Increasing rainfall has been blamed in part for the spread of disease amongst cocoa plants, particularly as Cote d’Ivoire experienced twice its normal levels of rainfall in July 2023 – unusual in the middle of the year.

The difficult conditions have prompted the International Cocoa Organization to predict an 11% decrease in global production this season, which Thijs Geijer, an economist at ING Research, tells Just Food would result in the lowest stocks in 45 years.

What are chocolate brands doing?

In good news for chocolate brands, Bergen explains the chocolate market remains healthy, despite the apparent decline in consumption.

“In the UK, around 95% of consumers buy chocolate once a week,” he says. “If you look at the whole year, chocolate consumption has declined – although not dramatically.

Chocolate has always been a lipstick effect for consumers

Edward Bergen, FutureBridge

“Chocolate has always been a lipstick effect for consumers; consumers may not buy a holiday or they may not buy a new car this year but they're still going to treat themselves to a piece of chocolate because that's a luxury.”

Yet brands are looking at other strategies to manage the increasing cost of cocoa. Products with higher cocoa content are seeing higher price tags, as big players look to limit losses, and several products have become the subject of ‘shrinkflation’.

When Mondelez reported its 2023 results in January, the branded chocolate and biscuits maker signalled there were still more price rises to come after a series of increases last year.

Volumes had so far remained relatively resistant as consumers prioritised snacking around favoured brands, despite two to three years of price increases by Mondelez, chairman and CEO Dirk Van de Put said.

In terms of chocolate in Europe, Van de Put said there was a “strong price increase of 12% to 15% in Europe” last year, with a “very limited” zero to 0.5% impact on volumes.

In Mondelez’s two-largest markets – North America and Europe – pricing has already been agreed for the new year in the former and the “majority” has been agreed in Europe, the CEO explained during a Q&A session with analysts.

Nevertheless, Van de Put suggested there might be some backlash in Europe to further pricing, as there was in 2023, as he indicated talks with some retailers are still ongoing.

“While the consumer is feeling better and more positive short term, we see that elasticity is still at or below historical norms, but there is some uptick in consumer elasticity in some spots around the world,” he added.

A spokesperson for Nestlé says: “While we are doing everything we can to manage these costs, in order to maintain the highest standards of quality, it is sometimes necessary to make adjustments to the price or weight of some of our products.”

Some companies are turning to cocoa substitutes or extenders, while others – including Hershey and, further up the supply chain, Barry Callebaut – have already announced layoffs.

Nestlé says: “Like every manufacturer of cocoa-related products, we have been experiencing significant increases in the cost of cocoa, making it much more expensive to manufacture our products.”

These expenses will eventually “filter through the value chain all the way to the consumer”, according to Geijer, who expects the trend of rising prices to continue.

Lindt & Sprüngli says it has “made a concerted effort to compensate for these increased costs by increasing efficiency as much as possible and through a forward-looking purchasing strategy. The remaining costs were subsequently passed on through price increases with the high cocoa price being the main reason for it.”

The Lindor chocolate maker has also indicated it plans to increase prices for consumers again this year, albeit at a slower rate than in 2023. Speaking to reporters – including Just Food – earlier this month, CEO Adalbert Lechner said Lindt's moves to up prices would be at a mid-single-digit rate and “substantially lower” than 2023.

Asked whether putting prices up again risked damaging consumer sentiment, Lechner said: “We are always cautious when it comes to price increases but our brands are very resilient. They are strong and have a loyal customer base. We don’t think we are overdoing it with price increases.”

Kevin Lee, the managing director at Belgium-based chocolate maker Guylian, adds: “Like other chocolate companies, the cost burden is increasing due to sudden chocolate price increases, and small and medium-sized companies like us are unable to directly reflect this in consumer prices.”

Will the tide turn on cocoa prices?

Nag warns: “Prices are going to rise because the climatic conditions are predicted to worsen further, with worse climatic conditions persisting over Ivory Coast and Ghana, which supplies almost 60% of the world cocoa supply.”

Longer term, she also notes the significance of regulatory pressures, as new laws that protect the environment (and therefore long-term cocoa production) also limit options for new cocoa farms.

The EU Regulation on Deforestation mandates that operators and traders must ensure that products are not sourced from recently deforested land and seeks to ensure that products sold in Europe do not contribute to forest degradation. There has been speculation this week that parts of the new rules may be delayed. Nevertheless, it is clear regulators want to make supply chains more environmentally sustainable.

Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana have lost 80% and 94% of their forests, respectively, over the last 60 years, with the World Economic Forum estimating that roughly one-third of the loss is attributable to expanding cocoa production.

Considering the possible recovery of the cocoa market, Stapleton concludes: “On a very simplistic level, if we've lost, say 8% of output, we can't expect prices to come back into balance until we've lost 8% of grindings. Demand has got to get destroyed in order for prices to be reined back. The big question is, how long is it going to take for that to happen? In the meantime, is there a point at which supply is going to start recovering again?”