This spring, Italian food group Barilla showcased a prototype for a 3D printer for its core product – pasta. The company is among those in the packaged food sector working out how it could use advancements in 3D printing technology. Brenda Dionisi talks to Barilla about its efforts so far and how it views the prospects for the technology.

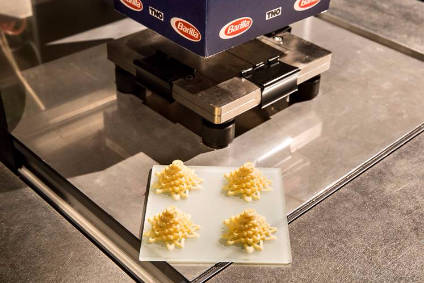

This year Italian food giant Barilla presented its latest technological innovation: a 3D printer that swaps ink for pasta dough and is able to make unique pasta shapes in just minutes.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Barilla is among the world’s first food producers to try to use the latest digital technologies and apply them to food production. Barilla has been working on a 3D pasta printing project for about five years now, which originated from a collaboration with TNO, the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research.

Previewed in May at the international food fair Cibus in the Italian city of Parma, Barilla’s 3D pasta-printer prototype is the world’s first 3D printer that can make fresh pasta. Today, the prototype can print four pieces of pasta in just under five minutes and a plate of fresh pasta can be printed in about 20-30 minutes, the company tells just-food. “When the project was first launched, the time needed to make the pasta was much longer – it was 20 minutes to print one piece of pasta and today we can print four pieces in about two minutes,” Fabrizio Cassotta, R&D research manager for meal solutions at Barilla, says. “We are now working to improve the time to print; our target is to print one full plate of pasta in two minutes.”

Thanks to 3D printing technology, there are numerous ways to shape pasta. Shapes are first digitally designed on a computer in pixels and the printer cartridge is filled with fresh pasta dough; then, at the click of a button, the digital design is sent to the printer and, in minutes, the fresh pasta pieces are printed in 3D.

In 2014, Barilla launched an international design contest, PrintEat, through the Italy-based 3D printing crowd sourcing online platform Thingarage, where the company was looking for pasta piece designs. Three pasta designs won the competition: ‘Moon’ (pasta in the shape of a full moon with ‘crater’ holes), ‘Rose’ (shaped like the flower) and ‘Vortipa’ (an elegant, sculptural pasta cone) – all of which can only be made with Barilla’s 3D technology.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“All these shapes have a specific uniqueness in terms of texture experience or functionality and are not possible with the traditional pasta-making technologies. For example, you can fill the ‘Moon’ shape to make a spherical, filled pasta, or experience a new pasta texture with “Vortipa” thanks to the complexity of its geometry,” Cassotta tells just-food.

The personalisation aspect of the technology is very important, affirms Luca Di Leo, Barilla’s head of global media relations. “It will allow consumers to not only design their own pasta shapes on the computer but also decide what exactly goes in the pasta, in terms of ingredients.”

The ingredient content of the pasta dough used in Barilla’s 3D printer cartridges does not change much from Italy’s centuries-old handmade pasta-making tradition – its two simple ingredients are durum wheat semolina and water. “We’ve had very good results with pasta dough made with water and semolina and we are now experimenting with other ingredients,” Cassotta says.

Based on the success of Barilla’s gluten-free pasta range, launched in 2013, the company is now taking those products into the realm of 3D printing, not only to make gluten-free and whole-grain pasta but also dough made with a mix of vegetables and pulses, Cassotta explains. “All of these experiences will help us better understand the limits of personalisation because there will probably be some limits. We cannot forget that 3D printing technology is still very new and we are the first company in the world to print 3D pasta prototypes. So it has been a real challenge to transform the standard 3D printing technology and apply it to pasta making.”

With Barilla’s 3D project still in the research stage, it will take some time to see Barilla’s 3D pasta-printing technology on the market. “What’s important to stress is that this is a medium-to-long-term project,” Di Leo says. “We are still at a very early stage and we are experimenting a lot and so it’s not something that we are ready to turn into a business application in a few months.”

It is difficult to say what the commercialisation prospects could be at such an early stage, Di Leo explains. “There are a lot of possibilities; as a starting point, we could potentially launch the 3D pasta-printer first at home or in restaurants. Barilla has four restaurants in the United States of America and we are going to open more there, and our restaurants could be a way of testing the printer.”

The first step will be to define the different business models and then the specific application of the technology, Cassotta adds. “As one could imagine, a 3D printer for the home would be very different from one used in a restaurant, particularly in terms of technical requirements.”

Cassotta also underlines that, while 3D pasta printing is developing much faster than some of other non-food 3D printing technologies, it is not comparable to the high speed and productivity of an industrial pasta line, thus production costs will probably be higher. “Just think that the 3D printer can produce four kilos per hour today versus the traditional pasta production line where we can produce from four to eight or nine thousand kilos of pasta per hour”, Cassotta says.

Those numbers make it highly unlikely that Barilla’s 3D pasta-printing technology could in the future supplant its traditional pasta ranges. “For sure, 3D-printed pasta will not replace the standard Barilla pasta which will always be the everyday pasta for everyone,” Di Leo says.

Nevertheless, Barilla is in the vanguard of those in the packaged food sector testing the technology.