In just-food’s latest in-depth focus, Ben Cooper looks at food companies’ efforts to put their west African cocoa supply chains on a truly sustainable footing.

If forecasts made around eight years ago had been correct, the world would imminently be facing a global shortage of cocoa. They were not correct.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

However, while not facing the crisis advertised, cocoa production is nevertheless at crisis point, firmly centred around the engine room of global cocoa production, Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, which produce around 60% of the world’s cocoa.

The struggle to put these supply chains on a sustainable footing is far from new. However, the challenge has intensified in recent years as a result of the primary reason for the forecast supply shortage not materialising – namely increased production of cocoa from illegally deforested areas.

Taking action on deforestation

“The increase in global cocoa production over the past few years has been attributable largely to the expansion of production often in protected environmental areas, which has created damage to the environment and ecosystems as well as pockets of over-supply that have outpaced current demand levels, therefore leading to a decline in global market prices,” says Richard Scobey, president of the World Cocoa Foundation, a trade body representing companies that buy around 80% of the world’s cocoa.

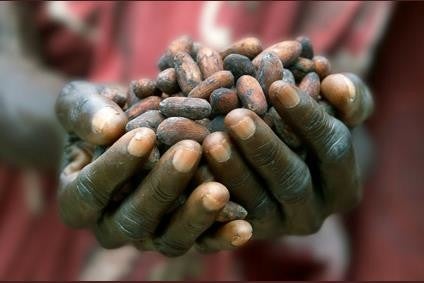

Deforestation in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana is unlike that seen in relation to other expanding commodities such as palm oil and soy. While there have been other contributors, deforestation in these two countries has been characterised by multiple small encroachments into protected areas by individual farmers as a means of boosting extremely low incomes. “Cocoa is a crop grown almost entirely by poor farmers on small plots,” Scobey continues. “So, given their limited economic opportunities many of them have encroached into the forest areas to expand the area under cultivation and to get more income for their families.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAs the root cause of deforestation is different from that seen elsewhere, the response has had to be innovative and unprecedented. The Cocoa and Forests Initiative, launched last year by the World Cocoa Foundation with other partners and companies representing more than 80% global cocoa usage, has two defining attributes that set it apart from the other multi-stakeholder and roundtable organisations set up to address deforestation in major commodities.

From inception, it has been conceived a public-private partnership, with key differentiated roles for the governments and the companies to perform. Secondly, it sets out to tackle the issue holistically, which means it addresses the needs of the farmers as a defining priority. The initiative, therefore, synthesises the aims of forest protection and restoration with creating sustainable cocoa production and protecting farmer livelihoods.

“To tackle the issue of deforestation in cocoa we really need the governments with us”

“I think what makes it different from initiatives in other sectors like soy and palm is that here from the outset we’ve tried to forge a partnership with the private sector and government,” says Daan Wensing, director of the landscapes and deforestation related commodities programme at IDH, the Sustainable Trade Initiative, which is a founding partner of the scheme. “To tackle the issue of deforestation in cocoa we really need the governments with us. This design gives us the best fighting chance to succeed.”

The task of reforesting parts of “forêts classées”, will be “a two-fold process”, says Simon Brayn-Smith, head of sustainability for Olam International’s cocoa operations. “The goal will not just be reforesting but also working with farmers to improve their productivity to take into account the shortfall experienced by reforesting part of those cocoa farms. It’s not a matter of saying we’re going to reduce the amount of cocoa by reforesting. It’s much more going to be about how you can improve productivity in other areas to counter-balance.”

While governments will be responsible for up-to-date mapping of forest cover and land use, compiling and sharing socio-economic data on cocoa farmers and their communities, and will assess and mitigate the social impacts and risks of any proposed land-use changes on affected communities, there are a host of actions companies will be undertaking.

“The private sector can help with productivity, with market access, with technical assistance, with access to finance, all the elements that are needed to create better livelihoods for the farmers,” Wensing says.

Scobey, meanwhile, is delighted with how the partnership is taking shape. “I’m extremely optimistic and excited about the level of ownership, trust and collaboration between industry and government on the actions that we’ve committed to.”

Traceability transformed

Among the most significant single undertakings to be made under the agreement by companies buying cocoa is to put in place verifiable monitoring systems for traceability from farm to the first purchase point for all their own purchases of cocoa. “Certainly with the issue of deforestation having risen up the agenda over the last year or so, traceability is now probably one of the biggest topics in cocoa,” Brayn-Smith says.

In April, Olam launched its At Source concept, a sustainable and traceable sourcing initiative aimed at providing detailed data on the environmental and social impacts of the commodities it sells. Olam is using GPS and other digital technology to map its farmer base in Cote d’Ivoire.

Brayn-Smith believes the company’s work on traceability has given it a “head start” in relation to the enhanced traceability commitments under the Cocoa and Forests Initiative.

“By the end of this year, we should know where 100% of our cocoa is coming from in Cote d’Ivoire”

“We have about 120,000 farmers that we’ve digitally registered but about 100,000 farmers that are GPS-mapped, and that’s work we’ve been doing actually over the last three years. So having that head start in being able to know exactly where are farmers are located definitely allows us to take a very positive step forward when looking at deforestation. It’s allowed us to identify exactly where our farms are, where they are relative to protected areas, to forest reserves. It’s allowed us to understand whether they’re operating in high-risk areas of deforestation and then to be able to do something about that. By the end of this year, we should know where 100% of our cocoa is coming from in Cote d’Ivoire and be able to identify whether or not any of that is coming from areas where it shouldn’t be.”

Nestlé, meanwhile, has set a target that, by the end of 2020, 57% of its cocoa will be sourced through its Nestlé Cocoa Plan. “We’re slightly ahead of that target and all that will be traceable to cooperative level,” a Nestlé spokesperson says.

Under the Cocoa and Forests Initiative, participating companies have committed 100% of the cocoa they buy will be traceable from the farm to the first purchase point by the end of December 2019.

In addition, the companies have committed to work with the origin governments to ensure an effective national framework for traceability for all traders in the supply chain. In Cote d’Ivoire, national traders account for 30-40% of the market. “We don’t yet have any national trading companies signed up to the Cocoa and Forests Initiative,” Scobey says. “A very important step and a challenge is to make sure the traceability system that we put in place applies equally to any company that buys cocoa. We’re not going to achieve our outcomes if we only have the 70% of cocoa purchased from the international trading companies.”

Boosting productivity and farmer income

Having spent the best part of two decades addressing the issue of child labour in their west African cocoa supply chains, the last thing food companies would have wanted is another high-profile sustainability challenge carrying significant reputational risk and demanding a huge collective response.

In many ways, however, the deforestation that has been seen in recent years is not a new sustainability concern but a further manifestation of the problem that underlies the issue of child labour and the stubbornly low productivity seen in both countries – that of farmer poverty.

Low productivity restricts farmer income, which in turn limits their ability to invest in materials to boost productivity, such as pesticides or fertilisers, or in farm development and rehabilitation. The motivation for farmers to expand into protected areas was to increase meagre incomes. Average yields in Cote d’Ivoire, in particular, are far below what they should be owing to poor farming practices and old cocoa trees well beyond their years of peak production.

Even if farmers can finance the purchase of new cocoa trees, it takes three to four years for the new plantings to produce any cocoa. Financing that is a daunting prospect given the poor financial returns cocoa farmers in west Africa can usually expect. A study conducted by the French Development Agency and chocolate supplier Barry Callebaut revealed Cote d’Ivoire cocoa farmers earn on average CFA568 (West African Franc) per day or around EUR0.86 directly as a result of low yields which were on average 435 kg/ha in 2016.

Cocoa Action, a collective programme launched by the World Cocoa Foundation and nine member companies in 2013, has a core goal to support 300,000 cocoa farmers to adopt its productivity practices. The target average yield for those 300,000 farmers (200,000 in Cote d’Ivoire and 100,000 in Ghana) by 2020 is 700 kg/ha.

The CocoaAction strategy splits farm programmes into three groups: Good Agricultural Practices (GAP), improved planting material and soil fertility interventions. As further reports are published, CocoaAction should be able to provide an ongoing quantitative measure of the level of farmer uptake of measures aimed at boosting productivity.

So far, however, the World Cocoa Foundation has only published benchmark data from 2016, which reveals 30% of CocoaAction farmers in Cote d’Ivoire and 23% in Ghana applied the required four out of five GAPs, including pruning. Other measures include pest and disease management and shade management.

The data collection and processing task is considerable but it would be fair to say that, in reporting at least, CocoaAction is some way off reflecting the dynamism its name might evoke. The World Cocoa Foundation was not able to give a 2017 figure on the number of farmers the programme had reached by the end of 2017, which would not presumably have required the most extensive number-crunching to obtain. In 2016, the participating companies had reached some 147,000 farms against the 2020 target to support 300,000 cocoa farmers in adopting CocoaAction productivity practices.

Reports vary regarding whether or not farmer engagement in farm improvement programmes is progressing. A spokesperson for Nestlé says although the latest figures from CocoaAction are yet to be finalised it “looks like there have not been significant improvements since 2016”. Nestlé points to the “difficulty in aligning data collection and the way in which fields are evaluated”. However, there had been improvement in these areas during 2017, the Nestlé spokesperson adds. Lower cocoa prices had also impacted negatively on farmer engagement.

To improve the situation, Nestlé makes a number recommendations: to use more and better demo plots, and bring farmers to see them; use more farmer coaching where appropriate; use innovative tools which get farmers attention better than existing methods, such as video; work with certifiers so that progressively farmers only gain premiums when they “genuinely change their practices”.

Jeff King, senior director of CSR and social innovation at Hershey, however, does believe engagement is increasing on good agricultural practices, whereas it is in the actions relating to soil fertility and farm rehabilitation, which require greater financial outlay, that engagement is more sluggish. “Good agricultural practices, of the three, are the ones that are catching on the most,” King says. “And then you get into farm rehabilitation, the last piece, we’re not seeing the uptake that we would want as much.”

“Some of these problems have been creating themselves over decade. It’s hard to believe we could solve them in a matter of years”

King concedes CocoaAction is “taking longer than we anticipated” but adds: “I believe CocoaAction is critically important and it’s going to take time. Some of these problems have been creating themselves over decades. It’s hard to believe we could solve them in a matter of years.”

Olam’s Brayn-Smith believes farmer support needs to be more tailored to the specific requirements of a farm. The agri-food giant is again putting its faith in digital technology, having developed a digital platform called the Olam Farm Information System (OFIS) that can facilitate a more tailored approach.

“It’s got to be targeted information for a farmer,” says Brayn-Smith. “What we need to do is have a much more targeted approach, to be going onto their farm, to help them with their specific problems, and to be doing that in the context of what we call a farm development plan. We’re able to give him [the farmer] a targeted plan specific to his farm. So it tells him exactly what he needs to do on his farm to improve productivity.”

Crop and business diversification

Another facet of farm development that differentiates current thinking and actions from many of the programmes of the past is the emphasis on crop and business diversification, which is also evident in the Cocoa and Forests Initiative.

“Diversification has to be a key part of any income strategy for farmers and that’s also something we work on quite a lot in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana,” Brayn-Smith tells just-food. Among the other commercial and agricultural activities Olam advises its farmers to consider are growing cassava, onions or yams and bee-keeping.

In a similar vein, Hershey’s King stresses the importance of business training for farmers. “Some of that farmer training is small business education from the standpoint of how to be a better small businessperson.”

Crop diversification provides some insurance against weak global cocoa prices but Wensing at the IDH points to what is perhaps an awkward truth for food companies as they seek to build a sustainable cocoa supply chain in west Africa, that even if farmers could double their income they would still be very poor and cocoa would still be the poor man’s crop.

“Even if we doubled the yields it still wouldn’t be a good source of income for farmers. Yes, of course, it would be better but it’s more than that. We really also have to look at diversifying the income of the farmer,” Wensing says.

The emphasis on a holistic approach to improving the performance, sustainability and livelihoods of the cocoa farmers that supply them pervades the range of concerted and individual actions being taken by food companies in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana.

The CocoaAction strategy has a corresponding social investment pillar with the goal to empower 1,200 communities through community development interventions. Scobey reports as of the end of 2017 around 1,000 communities had been reached. Women’s empowerment, primary education and child labour protection are the three focus areas within the communities pillar.

Once again, there is no more detailed information for 2017 but Nick Weatherill, executive director of multi-stakeholder body the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), says progress has been made on child labour. Underlining again the interconnectedness of cocoa’s economic, environmental and social challenges, Weatherill says cocoa’s performance on child labour is the “ultimate indicator for sustainability”, adding it remains “a prevalent problem but we are seeing progress”.

The strongest evidence for progress comes in the rollout of the ICI’s Child Labour Monitoring and Remediation System (CLMRS). The first company to adopt CLMRS was Nestlé and in 2015 it extended to 26,000 farms. By the end of 2017, it had risen to 91,000, with seven companies adopting the system, and ICI forecasts the number will reach 200,000 by 2020.

The rising importance of sustainability has meant higher sustainability standards can and are seen as a product differentiator. Cocoa is, in fact, one of the sectors where this can most clearly be seen, as chocolate is one of the categories where schemes certifying higher sustainability or ethical standards have been particularly successful.

Indeed, Scobey says the premium payment such schemes offer farmers, whether they are third-party organisations like Fairtrade or company initiatives, for cocoa that is certified as sustainable is “a very important step in the theory of change of accelerating the production of sustainable cocoa and creating a pathway for profitable and professionalised farmers.”

While there may be higher standards of sustainability for cocoa farmers to strive for, it is the base level – and the base farmer income – that has to be raised, as it is representative of a means of producing cocoa that simply cannot last.