Covid-19 has caused India’s packaged-food manufacturers to invest in the further automation of their production – and spending expected to endure beyond the end of the pandemic.

Increased demand for branded food products and workplace restrictions on industrial labour has sparked manufacturers into action and investment is forecast to continue, even among the country’s small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

“We have been getting a lot of orders from mom-and-pop kinds of smaller companies who were earlier shying away [from automation],” Raghav Gupta, director of Kanchan Metals, a supplier of food-processing machinery, based in Noida in northern India, tells just-food.

The pandemic, Gupta says, has persuaded companies who had been mulling whether to automate more, to buy equipment, with the company’s new machinery orders growing by 20% year-on-year during 2020.

Rupinder Singh Sodhi, managing director of Indian food major Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), which owns dairy brand Amul, says personnel pressures during Covid-19 have been a key driver of investment.

India’s packaged-food companies have always seen an increase in automation as a way to increase efficiency and reduce contamination but Sodhi says “Covid-19 aggravated the manpower shortage” seen across the industry. The large-scale reverse migration of industrial workers to their family villages last March at the outset of the pandemic created staffing problems that were not immediately resolved when the Indian government eased lockdown restrictions last summer, he explains. Even where staff are available, social distancing regulations imposed on factories have forced companies to produce food with fewer workers – and automation has been the quickest way to maintain output.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataNow, looking ahead to a post-Covid future, some companies believe markets have changed, and probably for good, in ways that favour the use of more machinery.

Girish Gupta, CEO of the Foodees Group of Consultants, in New Delhi, claims Indian food consumers have become more focused on health and on quality – and more automated production can help. He points out to the production of salty snacks, where he says when the foods are fried manually “the fat percentage increases” but can be lower when manufacturing is more automated. As well as appealing to more health-conscious consumers, products made on automated plants require less handling, so they will probably remain whole in packs, raising quality, he explains.

For larger companies able to afford more automation, there has been the ability to pass on lower costs to consumers. Good examples are small snack packs from companies such as Haldiram’s and Balaji Wafers costing INR5. “This leaves no advantage for the smaller manufacturers in the unorganised sector,” unable to compete on price or quality, Gupta says.

Smaller food manufacturers were already struggling, given they are now more exposed to taxation through the introduction of India’s nationwide Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017. Some have tried to borrow money or look for international partners to upscale, but many have failed and collapsed – a process hastened during Covid-19, which has worsened some companies’ weak supply chains and poor production quality.

Those able to afford automation, by contrast, have more efficiently processed materials, delivering better product quality and safety, shrinking worker numbers (and hence costs) and reducing factory lead times, Manu Tiwari, Gurgaon-based industry principal at research and consulting firm Frost & Sullivan, explains. “Automation also provides the ability to upscale or downscale production based on market demand forecasts,” he says.

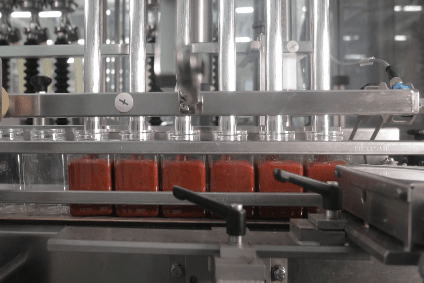

As a result, the adoption of automation has been broad-based in the past year, with Indian companies in the dairy, bakery, confectionery, processed fruits, vegetables, meat and poultry sectors all investing in automation, Tiwari points out. Packaging, sorting, grading and picking have all been particular targets of investment.

One section of work that has still remained focused on manual labour, however, has been packing products into boxes for bulk delivery, Oliver Mirza, the managing director and CEO of Dr Oetker’s business in India, says. Few Indian food manufacturers have fully automated cartoning lines, he says. “They employ labour to pack products into the cartons as it is more economical,” he tells just-food.

Where there is spending on automation in other parts of the production line, ideally the investment should be recovered in two or three years through reduced costs, Mirza suggests.

Domestic supply base

While automation has grown, Covid-19 has made the installation of new machinery a challenge, Mirza says, especially for equipment from overseas. “During the lockdown, we installed one locally-procured line for making Italian sauces that was critical for business,” Mirza says. However, plans to set up other imported equipment are “on hold due to the lockdown and quarantine restrictions in the suppliers’ home country,” he adds.

Given India’s strength in IT and software, it is possible more machinery could be sourced domestically, Frost & Sullivan’s Tiwari suggests. Automated solutions being made available locally for Indian food companies include supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) controllers, programmable logic controllers (PLC), advanced robotics and automated storage and retrieval systems, he says. “Industry 4.0 and ‘Internet of Things’ integration also support manufacturing systems to generate necessary analytics to self-correct [production] processes,” he notes – another potential strength of the Indian tech sector.

And more basic machines are being made to an adequate standard at affordable prices in India, says Piruz Khambatta, chairman of Ahmedabad-based food and beverage manufacturing business Rasna. Until ten years ago, almost every good food processing machine for making chocolate, noodles and food packaging were imported, but not any longer, he says. “Almost all dairy and snacks making equipment are made in India.”

Indeed, there is a wide range of locally-made machines that can fit tight budgets and variable consumer demand. “Potato chips lines [made in India] cost INR20m but there are also those available for INR1m,” Foodees’ Gupta says.

That said, Khambatta stresses that where cutting-edge hardware is more important – say with robotics driven by artificial intelligence – Indian food manufacturers will think of importing equipment from overseas suppliers. Khambatta, who is also the chair of the national committee on food processing for the Confederation of Indian Industry, says AI-driven robotics is especially under consideration for “controlling [the] moisture and quality parameters inside [food] manufacturing facilities”.

One encouragement for investing in overseas tech is India’s central government’s Export Promotion Capital Goods Scheme that allows the duty-free import of machinery that will make products for export, Khambatta says.

What is clear, however, is wherever they source machinery, India’s packaged-food companies are seeing value in investing in automation.

Himanshu Manglik, president of the Gurgaon-based consultancy firm Walnutcap and formerly a senior executive at Nestlé’s local arm in India, says once large systems are in place, companies can make smaller changes that give significant productivity gains.

“These could be simple – for example where and how best to place the sensors,” he says. “With swift changes and switch-overs, the existing lines can efficiently produce even small batches of new product variants.”

At Kanchan Metals, Raghav Gupta says automation can offer excess capacity for contract manufacturers to be able to swiftly orient production for a brand whose sales are booming, with demand exceeding supply. Such contracting offers important flexibility in a fluid packaged-food market operating against the backdrop of Covid-19.

Of course, the prospect of increased – and accelerated – investment in automation can lead to concerns about the fate of manufacturing jobs.

Proponents of automation sometimes suggest the technology does not necessarily mean mass redundancies and instead changes the nature of the work performed by human staff.

Manglik and Foodees’ Gupta argue most companies undergoing automation – especially larger manufacturers – want to retain their existing workforce by redeploying them in other processes like packaging or training them to upgrade their skills. Following investment in automation, production can rise substantially and there may be additional human tasks to undertake.

There will, of course, as in economies the world over, be some concerns about the impact increased automation may have on human staff in India’s packaged-food sector.