The Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have upended supplies through one of the world’s most important trade routes and caused companies across industries to reassess their logistics.

The retaliation from a US-led group of countries has added to the uncertainty in the region and supply-chain headaches have been further compounded by a drought affecting shipping through the Panama Canal.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

What is the issue in the Red Sea?

The Houthi movement, based in Yemen and backed by Iran, has been attacking cargo ships in the Red Sea heading for the Suez Canal for a number of weeks. While their stated aim is to target vessels heading for Israel in protest against that country’s actions against Hamas in Gaza, the attacks have become largely indiscriminate.

The US, supported by the UK, has retaliated by bombing Houthi sites in Yemen but, at the time of writing, the threat to commercial shipping using this route still exists.

Why should the food and beverage sector be concerned?

There is clearly a risk to trade.

Electric car maker Tesla has temporarily ceased production at its Berlin factory due to delays in receiving parts amid the attacks. Meanwhile, UK clothes retailer Next has warned supplies of its products could be delayed if attacks on container ships in the region continue.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataFood and beverage companies will be well aware Russia’s blockade of Black Sea ports following its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 impacted the supply chain for ingredients such as wheat and edible oils and contributed to the high-inflation climate they operated under last year.

The Red Sea/Suez Canal is a big deal in world trade terms. It is said to handle 12% of global trade while the Suez Canal accounts for nearly a third of the world’s container traffic. The re-routing of ships carrying goods from the near and Far East to Europe and beyond means vessels are travelling 3,500 extra nautical miles around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

It's feared the additional fuel cost alone could lead to price increases in supermarkets, while the delays caused by the extra travel time – estimated to be up to two weeks – could cause stocking issues or even result in spoilage.

Ships using the Red Sea are also facing a hike in insurance payments and are having to pay crew members higher salaries – in effect ‘danger money’.

As a result, it seems inevitable food and beverage businesses dependent on supplies via the Red Sea will be exposed to higher costs for energy, chemicals and packaging. Oil prices jumped by 4% after the US and UK launched strikes in Yemen.

In a paper published on Tuesday (16 January), Dutch banking and financial services group ING said the increased tension poses supply risks, with energy markets most vulnerable.

In the first week of January, 220 fewer ships took the Red Sea route than in the first week of January in 2023, according to ING.

Maersk, the Danish shipping giant, for example, announced the suspension of sailings by its vessels through the Red Sea with CEO Vincent Clerc telling the UK’s Financial Times newspaper “at this time when inflation is a big issue, it’s putting inflationary pressure on our costs, on our customers, and ultimately on consumers in Europe and the US”.

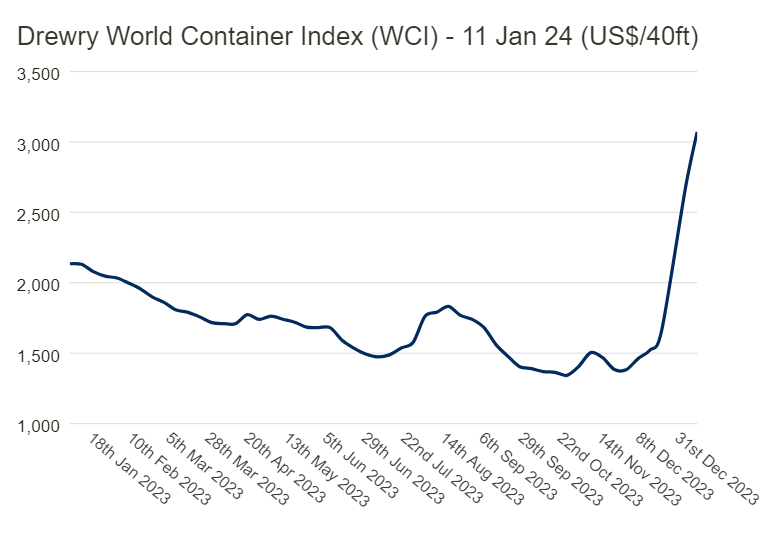

Maritime research and consulting group Drewry has reported a jump in the cost of container freight. Its most recent update, published on 11 January, showed a 15% increase in the cost of a 40ft container. Compared with the same week last year, the price jumped 44%.

What has been the immediate impact?

There’s no sense of panic in food and beverage supply terms. Helen Dickinson, chief executive of the British Retail Consortium, said: “While the ongoing challenges through the Red Sea could mean some delays on the supply of products coming from the Far East, such as electronics, furniture or DIY goods, it is unlikely to affect food imports, which tend to come in via the EU.

“Over the coming months, some goods will take longer to be shipped, if they are re-directed via longer routes and there could be a knock-on impact on availability and prices as a result of higher transportation and shipping insurance costs. Retailers will work hard to ensure their customers are not affected."

Italian farmers’ organisation Coldiretti, though, has concerns about the impact on exports of the country’s produce.

“The destinations involved are Asian ones, to which Italy has exported over 217 million kilos of fruit, of which over 182 million kilos are apples, with the main destinations being Saudi Arabia (over 66 million kilos of apples), India (over 51 million kilos of apples) and the United Arab Emirates (over 15 million kilos of apples),” it said, quoting 2022 data.

Coldiretti is also concerned about its wine trade, worth €112m ($121.8m) annually in exports to China alone.

“The blockade of the Red Sea therefore puts Made in Italy exports to China at risk, which for the agri-food sector alone are worth more than €570m per year, of which over 90% travels by ship,” it said.

Meanwhile, the organisation EastFruit said the “most significant blow” to the international fruit import-export trade will be between the countries of Europe and North Africa with Asia and a number of countries in the Middle East.

“In particular, Egypt is currently experiencing pressure on the prices of citrus fruits and a number of other fruits and vegetables that have traditionally been exported to the UAE, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries, as well as to Asian countries,” it said.

EastFruit also notes the cost of logistics and transfer times increasing significantly has impacted the exporting of apples from countries such as Ukraine and Moldova to the countries of the Middle East.

And it points to problems for suppliers from Turkey, which is one of the largest trading hubs for fruits and vegetables in the region.

In the UK, Ken Murphy, CEO of Tesco, the country’s biggest supermarket group, has also expressed concerns. He told reporters last week: “If they [cargo ships] do have to go the whole way around Africa to get to Europe, it extends shipping times, it constrains shipping space and it drives up shipping costs.

“So that could drive inflation on some items, but we just don’t know.”

What are industry watchers saying?

Speaking about the UK, Marco Forgione, director general of the Institute of Export & International Trade (IOE&IT), noted the UK’s more promising recent economic news could be undermined by the harm caused to the world economy by the disruption in the Red Sea.

He said: “We are about to see increases to pricing in supermarkets as it’s the products that are coming through now that have been impacted.”

The UK’s i newspaper reported that an unnamed senior Indian government official told a newspaper there that the disruption could raise the global export price of basmati rice by between 15% and 20%.

Aaron Hanson, a senior economist and analyst with GlobalData – the parent company of Just Food and Just Drinks – suggests the coffee sector could take a hit.

He said: “It [the Red Sea crisis] could have a significant impact on the coffee industry primarily Europe – but not necessarily in terms of pricing. Rather, with the EU being the single largest coffee-consuming region, and with a record high share of this currently taking the form of robusta beans – used primarily in instant coffee, but increasingly blended into ground coffee products – and with the vast majority of these coming from East Africa and South-East Asia, it means the turmoil is likely to quicken the pace of a reversion back towards higher arabica levels in European coffee blends.

“So the likely impact is really within the industry in order to avoid pricing impacts.”

Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at German financial services giant Allianz, told UK broadcaster the BBC that inflation is at risk of rising again.

"Relative to what would have happened otherwise, we will see higher inflation, higher mortgage rates and lower growth,” he said.

However, ING suggested this week that agricultural flows are less likely to be significantly disrupted by developments in the Red Sea than oil, gas and metals such as aluminium (used in packaging).

“Saying that, however, we have been seeing increased volumes of US grain taking the longer route via the Suez Canal and onwards to Asia, rather than through the Panama Canal,” it said.

“These increased flows have come about due to the ongoing restrictions at the Panama Canal. Obviously, voyage times will increase further if these shipments now have to avoid the Suez Canal and go around the Cape of Good Hope.

“In addition, there are several standalone sugar refineries in the Red Sea, which may find it more difficult to export containerised refined white sugar due to container ships avoiding the region. This could potentially lead to some tightness in several domestic markets within the region and parts of Africa. Obviously, this is not only applicable to sugar. A number of containerised agri-commodities could see disruptions as a result.

“There are also potential indirect impacts from the Red Sea attacks on agri-markets. If they persist and lead to increased delays, farmers could see their input costs increasing. This would materialise in the form of higher diesel prices and potentially higher fertiliser prices.”

How have food and beverage companies reacted?

Keeping a watching brief and/or taking seeking alternative trade routes might be a fair way of summing it up.

New Zealand dairy heavyweight Fonterra – the world’s largest dairy exporter – said it has been working closely with its logistics partner Kotahi and customers since the disruptions to shipping lines began at the end of last year.

Santiago Aon, the company’s director for global supply chain, said: “Carriers are now going around the Cape of Good Hope, which means transit times will increase by 14 to 17 days.

“It is very likely these changes will result in congestion and delays for some time and detail of those impacts will become clearer over the next few weeks.

“This is a very fluid situation that changes daily but through Kotahi we have arrangements in place with key partners to prioritise and manage orders through the network. This will continue through this period of disruption.”

Dutch dairy cooperative FrieslandCampina tells a similar tale but also has concerns about the impact on costs.

A spokesperson said: “Confronted with the recent disruptions in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, our carrier partners have largely chosen to re-route shipments via the Cape of Good Hope to its destinations. This adds ten to 15 days of transit time depending on the destination. Both finished goods and incoming material flows have been impacted.

“Transit via the Cape of Good Hope is more expensive compared to the Suez route. Longer transit times require more fuel and decrease available capacity. We are working with our carrier partners to ensure the continuity of our operations. The cost per container could potentially increase by 30% to 70%, resulting in a range of up to $3,000 per container, depending on the destination.

The spokesperson added: “To date, we have been able to minimise the impact through safety stocks and priority access to vessels and equipment.”

Australian wine major Treasury Wine Estates said: “We’re monitoring the evolving situation closely and will continue to work with our shipping partners to meet customer orders in a timely manner.”

Japanese brewer Kirin, meanwhile, said there has been no major impact [on exports] at this time. But it added: “If it is prolonged, there is a possibility that it may be affected in the future. Details are being confirmed.”

Its local peer Asahi told us: “As of now, we have not seen any significant impact on our overall group business. Although there have been some disruptions, including delays in the transportations of products and raw materials due to changes in shipping routes, we have been minimising these effects through measures such as inventory adjustments.”

Danish beer giant Carlsberg, meanwhile, said it has seen a “minimal effect” of the situation in the Red Sea as most of its products are produced locally in its different markets or in regional hubs.

What happens next and what further action can companies take?

Unlike the Black Sea blockade situation – where retaliatory attacks on Russia by western powers were never going to happen – countries such as the US and UK believe they have the firepower, and the freedom to act, to negate the Houthi threat, downing incoming drones and missiles and hitting targets on land. Whether shipping companies would consider such measures enough of a safety net to resume moving goods through this area, given that military analysts are saying that the Houthis themselves have a considerable and sophisticated weapons arsenal, is another matter.

The Israel/Gaza situation could stabilise, which might dampen the Houthis’ enthusiasm for what it sees as retaliatory strikes, but no one is holding their breath.

As we have seen, some food and beverage manufacturers are already looking for alternative routes. News agency Reuters points out that French dairy heavyweight Danone has already diverted most of its shipments and has said that if the situation last beyond two to three months, it will activate mitigation plans, including using alternate routes via sea or road wherever possible.

In a statement to Just Food, Danone said: “There has been no significant short-term impact reported on Danone’s activity. We are closely monitoring the situation, in relationship with our suppliers and partners, and have put in place mitigation plans.”

Nevertheless, it’s hard to imagine that any company with a significant import/export operation encompassing the region is not engaged in working through different scenarios.

Apart from taking the long way around for its shipments of goods, there may be the possibility of new routes that combine land and sea. Ukraine has worked around the Russian blockade of its main Black Sea ports by using other departure points that are harder for Moscow to block and by increasing exports over land.

Food and beverage manufacturers could also try and find alternative sources for supplies that use safer shipping routes. This could, potentially, benefit regions such as South America in terms of ingredients such as palm oil, sugar, cocoa beans, coconut milk, exotic fruits and spices.